Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt.

“There are tears of things, and mortal things touch the mind.” — Virgil

B. Gowin – Lovely old cemetery at San Gabriel Mission

22 Sunday May 2016

Posted in Artful

Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt.

“There are tears of things, and mortal things touch the mind.” — Virgil

B. Gowin – Lovely old cemetery at San Gabriel Mission

28 Sunday Feb 2016

I’ve never been crazy about the mass produced “art” that’s cranked out for the purpose of matching your sofa. Though sometimes colorful and pleasant in its own limited way, at its heart, it’s banal and expressionless. It communicates nothing. And what a shame that so many of us settle for this kind of visual poverty in our homes. By doing so, we choose to forgo the enrichment that more meaningful art can provide for us.

But at the same time, I’m not of the opinion — so prevalent in today’s art world — that if works are “pretty” in the obvious sense of the word, they are automatically less important or are socially irrelevant. That is, quite simply, bunk.

A quick journey through art history reveals that each new movement has been, in large part, a reaction to the one before. Works are products of their time, and many are tied inextricably to powerful sociopolitical changes and brilliantly reflect these. But even the less outspoken, more purely aesthetic pieces are never completely devoid of meaning or expression, because they are always filtered through an individual artist’s unique sensibilities and personal voice.

Illustration: Barbara Gowin

And while no period in art can or should be without its larger overriding intellectual philosophies, there’s no denying that certain pieces will always speak to us in a more simple and direct way, regardless of their period. What I’m talking about here is the sensuous pleasure of aesthetics simply for aesthetics’ sake. A gut response of … “Wow! That’s lovely.” This is something we all, universally, like to feel.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that our historical love of ornamentation, seen so often across cultures in earlier centuries, flourished for so long in both art and craft. It survived the scientifically savvy age of enlightenment and beyond, well into the twentieth century. There persisted a juxtaposition of the ornamental with the functional, as if we simply could not bear to relinquish its pleasing forms. We held onto decorative beauty just as long as we could before it was replaced by the inevitable form-follows-function approach that we take for granted today.

And while I appreciate the clear, strong lines of the mid twentieth-century aesthetic as much as the next boomer, I find I also miss the visual richness that it has systematically stripped away, so that mass-produced minimalism and efficiency are so often our goals today. But though this is an integral part of where we’ve come and who we are, we shouldn’t forget that there can always be more.

And what is more? Satisfying complexity. Exquisite color palettes. Voluptuous textures. Sensitive, vibrant rendering of natural forms. But also a kind of fourth dimension … one of emotion, inspiration and, sometimes, transportation to another place and time.

John Everett Millais – The Eve of St. Agnes Via: Wikimedia Commons

John Atkinson Grimshaw – At the Park Gate Via: Wikimedia Commons

Lately, my favorite travel guides are from the eighteenth and late nineteenth centuries. These artists lead me through fantastic landscapes, gardens, boudoirs and bowers. Golden Age illustrators fly me to fairy tales and fantasies. And all of them treat me to a remarkable world of beauty and imagination.

Arthur Rackham – Frog Prince Via: Wikimedia Commons

John Atkinson Grimshaw – The Lady of Shalott Via: Wikimedia Commons

It’s a world I’d never deeply explored because of my own personal bias against the pretty. I thought that pretty meant silly, superficial. Pretty meant unsophisticated. But now, I say we all need a break from the ugly, a little softness around life’s sharp contemporary edges.

And besides, art is a moveable feast … so why not dine sumptuously?

________

Following illustrations- Barbara Gowin:

11 Monday Jan 2016

Posted in Artful

The invention of photography profoundly changed both art and science, forever altering our way of representing and archiving our world. We may take its value for granted now, but after its birth, photography created tremendous controversy before finally becoming accepted as the expressive and versatile medium it is today. While its more practical uses were quickly adopted, it took years of exploration and experimentation for us to tap into the true depths of its artistic potential. It’s an aesthetic adventure we still continue today, the instant gratification of modern photographic technology giving us even greater incentive to capture, illustrate, and create.

The Dawn of Photography

The earliest to perfect the photographic process were Joseph Niepce and William Talbot, both scientists, and Louis Daguerre, a painter who had a long-time working partnership with Niepce. All of them experimented with complex chemical processing methods, each making their own unique and vital contribution. But it was the culmination of Daguerre’s work in 1839, the daguerreotype photograph, which first created tremendous public awareness and enthusiasm, a veritable “daguerreotypomania.”

Today, it’s hard for us to imagine what an absolute novelty it was to gaze at a photograph. Such a novelty, in fact, that when Talbot published his 1844 book, “The Pencil of Nature,” it became the first publication in history to be illustrated with photos. This viewing experience was so new that Talbot, in his introduction, had to remind his readers that his plates were

…impressed by the agency of light alone, without any aid whatever from the artist’s pencil. They are the sun-pictures themselves, and not, as some persons have imagined, engravings in imitation.

Talbot proceeded to make great efforts to protect the rights to his own photographic method, the calotype or talbotype. But in the end, it proved impossible to compete with the daguerreotype’s technical and aesthetic superiority. The French government eventually purchased Niepce’s and Daguerre’s rights to their new process. Comprehending its profound importance, France then released it, worldwide, without patent. A new visual revolution had begun.

Growing Pains

Early photographs were met with vehement protests by many, ranging from lofty philosophical objections that they were an insult to God to more down-to-earth aesthetic complaints about their graphic and, at times, downright ugly honesty.

But many forward-thinking enthusiasts were thrilled at the exciting potential of the new invention. Edgar Allan Poe, himself the subject of a number of well-known and iconic daguerreotypes, wrote several periodical essays in 1840 devoted to the subject. He felt adamantly that these new, truthful images provided a kind of insight into human nature itself, and “…must undoubtedly be regarded as the most important, and perhaps the most extraordinary triumph of modern science.” And as their popularity grew, an ever-increasing number of the population became able to view and purchase these images for themselves.

Via Wikimedia Commons Source: Wonders & Marvels

But one important impediment to public access still remained. Creating a daguerreotype was a very specialized and labor-intensive process, involving knowledge of complex arcane procedures and the use of potentially dangerous chemicals. This meant that only a relatively few expert photographers were able to actually take and develop their own photos.

Then entered George Eastman, American philanthropist and entrepreneur, who perfected the first practical roll film and produced the Kodak camera in 1888. This standardized the process, and its ease of use now made it accessible, virtually overnight, to anyone. No longer was photography in the exclusive domain of a handful of highly skilled individuals with very specialized abilities. It now belonged to amateurs and professionals alike.

Art or Science?

This new ubiquity deeply fanned the flames of an already intense debate within the artistic community about whether photography could ever truly be considered an art form. There were many who felt it would always remain simply a product of inexpressive and passionless chemistry. But this longstanding and heated controversy would continue to rage on in vain as photography began to quietly but profoundly change the way we creatively see our world.

Perhaps nowhere was this change in vision more clear than in the work of the Pre-Raphaelites. Originally founded in 1848, this brotherhood of artists shunned classical mannerist painting and revered historical periods of art before the appearance of such artists as Raphael and Michelangelo. They were heavily influenced by the aesthetics of 15th-century Italian art and were moved by the ideals of Romanticism and the spirituality of the medieval period. Nature was also of the utmost importance, and they believed that very careful rendering and “mimesis,” the accurate imitation of natural forms, were crucial to the message they wished to convey. Like the early photographers, they searched for new and creative ways to employ realism. But as a reaction to photography, they were challenged to take their painting to philosophical and symbolic realms beyond its reach. The result was a strongly photorealistic quality to their dream-like work, made almost hyper-real through their intense attention to postures, textures and details.

John William Waterhouse – The Crystal Ball Via: Wikimedia Commons Source: WikiArt

The impressionists also felt the strong impact of the photographic revolution. As they pushed the boundaries of conventional visual art, many painters took advantage of a new vocabulary of photo-like effects such as motion blur, the use of new and dramatic angles of view, and the extension of subjects beyond a painting’s boundaries. And as the ordinary subject matter of most photographs began to foster a new interest in the everyday activities of common people, many impressionists responded in kind by focusing on such egalitarian themes in their own work. Exploring in parallel evolution with the photographers of their time, each found brand new ways of creating a sense of spontaneity and expressing the truth of captured living moments, frozen in time.

Gustave Caillebotte – Segelboote in Argenteuil Via: Wikimedia Commons Source: The Yorck Project

Yet other artists, still unmoved by the starkness of early photographic imagery, began to use photos simply as reference sketches for their paintings, building on that strictly representational material and turning it into a more subjective and expressive work. But gradually the tables turned, and conventional concepts and sensibilities of fine art now, for the first time, began to impact photography.

The Poetry of Pictorialism

A fascinating artistic movement arose in the late 1800’s now known as “pictorialism.” This would prove to be the first important turning point in the development of photography as an art form, demonstrating to viewers that it was now capable, definitively, of being more than just a means to record reality.

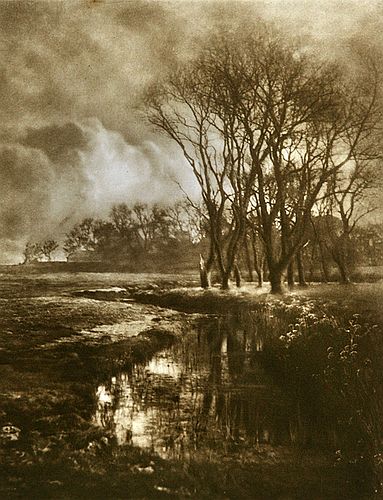

Searching their way through this still-new medium for a means of greater expression, a small circle of like-minded photographers strove to create what they saw as more evocative, artistically relevant work. During the last decade of the 19th and on into the early 20th century, this movement blossomed into international prominence as a growing number of pictorialists found new and ingenious ways to imbue their subjects with sentiment and imagination. They experimented with creating a sense of atmosphere to soften harshness, using soft focus and choosing sepia or blue tones rather than basic black and white. They carefully adjusted tonality to further enhance a sense of mood. In effect, they distanced viewers just enough from the subject matter to allow them room to use their imagination, thereby giving them a more active role in the artistic process.

Motif from Suffolk – Alfred Horsley Hinton Via: Wikimedia Commons Source: Luminous-Lint

Fast Forward

The initial allure of the pictorialist movement gradually began to fade by around 1920. Modernism, with its emphasis on sharp focus, changed aesthetic tastes and rendered its sensibilities old fashioned. Even the great fine art photographer Alfred Stieglitz, one of pictorialism’s most fervent creators, eventually rejected its methods for their inherent artifice. He went on to help establish a more modern approach to the medium, feeling that photography could be impactful on its own, through the skill of the photographer himself, without resorting to darkroom tricks. Fine art photography was now maturing and moving in a new direction through great photographers like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, to be followed in turn by the well-known portraiture and photojournalistic artists of the later 20th century and beyond.

But there has now been a resurgence of interest in the earliest photography. Many of us have found joy in rediscovering both the romantic creativity of pictorialism and the poignant realism of daguerreotypes. And though this may seem anachronistic, it really makes perfect sense amid the endless expressive possibilities available in our contemporary world of digital cameras, phones, and processing apps. Though many of the techniques and effects of the early photographers are naive by today’s standards, with a quaintness that is an inevitable result of being a product of their time, their sheer inventiveness and raw freedom of expression still speak to us. As pioneers ourselves, their ground-breaking discoveries resonate with us as we continue to invent, as they did, even more compelling ways to create photographic art.

Nature’s pencil will never stop sketching as long as new inspiration and technology await.

Photo: Barbara Gowin