Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt.

“There are tears of things, and mortal things touch the mind.” — Virgil

B. Gowin – Lovely old cemetery at San Gabriel Mission

22 Sunday May 2016

Posted in Artful

Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt.

“There are tears of things, and mortal things touch the mind.” — Virgil

B. Gowin – Lovely old cemetery at San Gabriel Mission

27 Sunday Mar 2016

Posted in Museful

B Gowin

When I was a child, my back door opened to a new world that filled my eyes with wonder and my head with daydreams. It was a space for dramatic plays starring the garden statues, staged under the huge elm tree. A soft and grassy playground for leaping through sprinklers, pink swimsuit ruffles soaked and drooping. My backyard gave me summer friends and flowers and morning promises of what each new day might bring. It was a place where baby dolls became Barbie dolls and dreams of a grown-up life that would come all too soon.

It was a little green world of firsts and lasts: First birthday party, first kiss. Last day of school … and last day with my father.

This yard was his kingdom. It was the balmy California antidote to a chilly Bronx Depression. Far from the restless streets of New York, he made his own mid-century Shangri-La, full of golden bamboo and crimson camellias. Young fruit trees brought him oranges and figs while sweet olive and jasmine thrived beneath windows, and perfume filled the house. My father created a private and peaceful tropical haven where he could love his wife and raise his little girl and where for over forty years, he cherished each stolen moment, until there were no more.

I still miss him.

And in its own wild way, the garden mourned his loss. Destined for firewood, the mighty elm faltered, elderly and spent. The peach tree offered one last golden harvest and soon it, too, was gone. Now, so long orphaned, the aging bird of paradise gives up its struggle with the ivy, and the rye no longer battles the crabgrass.

In the chilly winters, outside the dusty porch screen lies a still and slumbering Eden. But deep within this timeworn arbor, far beneath the roots and the sand and the clay, the rhythm of a strong old heart keeps time. For though gardens may sleep, they never forget, and they repay the life they’ve been given tenfold.

With each new spring, the garden wakes, and through its living world Dad speaks to me once more. Vintage roses reappear and climb to the sky. Incense of old jasmine stirs the night air. The faithful orange opens its heady blooms, and for yet another season, their nectar will tempt the honeybees. For yet another summer, new finches and doves will fledge. In this suburban wilderness, countless creatures have found a home, and still more tiny lives will always find green shelter and haven.

And so will I.

For I am the lucky guardian of Dad’s ancient realm. And though its restless flora and fauna transform with each passing year, for me, the most important essentials forever remain: Each day, the California sun still makes its morning promise; and my father’s love, in every stem, leaf, and bud, still rules this little kingdom beyond my back door.

28 Sunday Feb 2016

I’ve never been crazy about the mass produced “art” that’s cranked out for the purpose of matching your sofa. Though sometimes colorful and pleasant in its own limited way, at its heart, it’s banal and expressionless. It communicates nothing. And what a shame that so many of us settle for this kind of visual poverty in our homes. By doing so, we choose to forgo the enrichment that more meaningful art can provide for us.

But at the same time, I’m not of the opinion — so prevalent in today’s art world — that if works are “pretty” in the obvious sense of the word, they are automatically less important or are socially irrelevant. That is, quite simply, bunk.

A quick journey through art history reveals that each new movement has been, in large part, a reaction to the one before. Works are products of their time, and many are tied inextricably to powerful sociopolitical changes and brilliantly reflect these. But even the less outspoken, more purely aesthetic pieces are never completely devoid of meaning or expression, because they are always filtered through an individual artist’s unique sensibilities and personal voice.

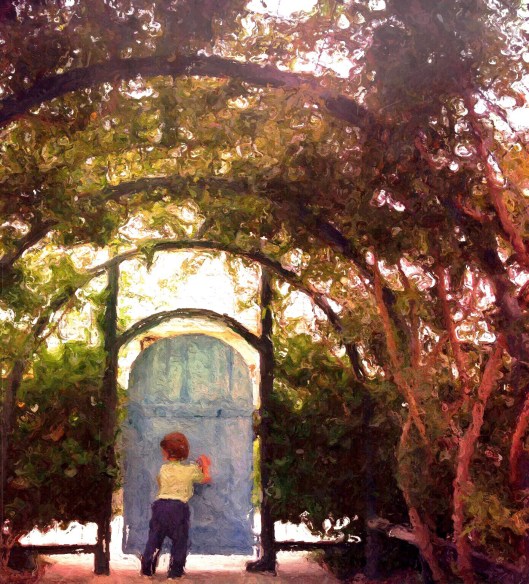

Illustration: Barbara Gowin

And while no period in art can or should be without its larger overriding intellectual philosophies, there’s no denying that certain pieces will always speak to us in a more simple and direct way, regardless of their period. What I’m talking about here is the sensuous pleasure of aesthetics simply for aesthetics’ sake. A gut response of … “Wow! That’s lovely.” This is something we all, universally, like to feel.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that our historical love of ornamentation, seen so often across cultures in earlier centuries, flourished for so long in both art and craft. It survived the scientifically savvy age of enlightenment and beyond, well into the twentieth century. There persisted a juxtaposition of the ornamental with the functional, as if we simply could not bear to relinquish its pleasing forms. We held onto decorative beauty just as long as we could before it was replaced by the inevitable form-follows-function approach that we take for granted today.

And while I appreciate the clear, strong lines of the mid twentieth-century aesthetic as much as the next boomer, I find I also miss the visual richness that it has systematically stripped away, so that mass-produced minimalism and efficiency are so often our goals today. But though this is an integral part of where we’ve come and who we are, we shouldn’t forget that there can always be more.

And what is more? Satisfying complexity. Exquisite color palettes. Voluptuous textures. Sensitive, vibrant rendering of natural forms. But also a kind of fourth dimension … one of emotion, inspiration and, sometimes, transportation to another place and time.

John Everett Millais – The Eve of St. Agnes Via: Wikimedia Commons

John Atkinson Grimshaw – At the Park Gate Via: Wikimedia Commons

Lately, my favorite travel guides are from the eighteenth and late nineteenth centuries. These artists lead me through fantastic landscapes, gardens, boudoirs and bowers. Golden Age illustrators fly me to fairy tales and fantasies. And all of them treat me to a remarkable world of beauty and imagination.

Arthur Rackham – Frog Prince Via: Wikimedia Commons

John Atkinson Grimshaw – The Lady of Shalott Via: Wikimedia Commons

It’s a world I’d never deeply explored because of my own personal bias against the pretty. I thought that pretty meant silly, superficial. Pretty meant unsophisticated. But now, I say we all need a break from the ugly, a little softness around life’s sharp contemporary edges.

And besides, art is a moveable feast … so why not dine sumptuously?

________

Following illustrations- Barbara Gowin:

03 Wednesday Feb 2016

Posted in Healthful, Scienceful

Grace sits comfortably in her well-padded wheelchair, enjoying dinner. The California sun slants low through her nursing home window and before she’s finished, slips down the backs of the west valley hills. She eats her food slowly, but Mom is a bright 91-year-old lady who’s really still quite sharp. And although she struggles with dimming vision from macular degeneration, she finishes her meal by herself and is now feeling content and talkative.

So we begin to share all the latest gossip in that close, confidential way mothers and daughters often do. We talk of friends and relatives, of news and memories. This always gives Mom great pleasure, and it’s only after twilight falls and we exhaust these happy topics that she turns toward darker concerns. Old age. Recurrent bouts of illness. And coming to terms with not being able to see faces anymore, recognizing those near her now by size, a characteristic walk, a familiar voice.

It’s medication time. The nurse comes in. Mom, now a pro at this, swallows all her nighttime pills with one big gulp and settles in for the evening. Elizabeth wishes us a good night as she clears the dinner dishes. After kindly asking if there’s anything else we need, she hurries home to her own family, and Mom and I are alone again in her room.

After a long pause, double-checking that the doorway is still empty, Mom leans closer and confides something that’s troubling her. She hesitates. “You know,” she whispers, “I don’t want to say anything to anybody, because it sounds…well, crazy…but I’ve been kind of…seeing things sometimes.”

Oh, God. “Seeing things,” as we all know, is rarely a good thing.

I try to sound nonchalant. “Really, Mom? What kinds of things?”

“Shapes. Bright fields of diamonds and colored filigree patterns. Oh…and a girl’s face! She wears the most beautiful old-fashioned bonnet!”

I sit transfixed by the coincidence. At bedtime the night before, I had been reading a book by neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks. He described an exotic-sounding disorder with a unique assortment of odd hallucinations, and it’s uncanny how these visions coincide with Mom’s description. It’s as if she has just read the same chapter, too.

I ask her for more details. And as we talk on into the evening, she tells of fantastic flowers fading in and out of view. Bright honeycomb-like hexagons creeping up the walls. She has seen brilliant points of light, hundreds of them, scattered over the ceiling like great fields of stars. Ornate filigrees which, she marveled, were much more detailed than anything she would ever have seen in real life. And most peculiar of all, that strange girl. Just a floating head and face of a young woman with elaborate, ringleted hair and an amazing lace-filled Victorian hat.

Mom is very animated, clearly relieved to finally tell someone about this. But she turns thoughtful for a few moments. “I know they’re not real, but I see them so clearly. I’m worried I might be losing my mind.”

I smile reassuringly, though I know she can’t see it. “No Mom! You’re not crazy!…but I think you might have Charles Bonnet syndrome.”

_____

Once you learn about this syndrome, “CBS,” it’s the crazy nature of its hallucinations that stick in your memory. These strange visions were first noted in 1760 by Charles Bonnet, a Swiss naturalist. He observed them in his elderly grandfather, a man suffering from failing eyesight but still quite mentally sound and able to describe his apparitions in detail. Recognizing their probable connection, Bonnet was the first to record such a relationship between hallucinations and vision loss. But it was largely forgotten in the literature, and it wasn’t until 1982, in the field of psychiatry rather than general medicine, that the syndrome’s name was officially coined. And even today, many physicians and nurses are not well acquainted with its eccentric yet specific set of signs and symptoms, so consistent across those who experience them.

First, there are the so-called simple hallucinations. These may manifest as spots of colored light, grids, mosaics, or other repeating geometric or ornamental patterns. Most people with CBS will see at least one of this type at some point. Others may see scraps of text, long strings of numbers, or nonsensical musical notation. A smaller number of people will experience more complex hallucinations. These can be of animals or scenery, but most frequently they involve people, or even just faces. They are usually soundless and often dressed in elaborate garments and hats, like the one worn by the young girl my mother “sees.” Adding to their eeriness, certain facial features may be very distorted or exaggerated, especially the eyes or teeth. And if the hallucinator still has some remaining vision, these images can superimpose themselves onto the existing surroundings, creating a kind of virtual reality and a very confusing situation for the sufferer.

But perhaps the most striking thing about these images is their typical complexity. They often have a level of detail much finer than we’re able to see in the real world. It’s as if these visually impaired individuals have an “inner eye” that’s capable of perceiving much more extraordinary resolution than their “outer” ones ever could. And this might not be far from the truth.

CBS’s unique phantasms are known as “visual release” hallucinations. While the exact mechanism is not clearly understood, they are thought to reflect the brain’s adjustment to lack of real-world input from the eyes. They may represent our memory of primitive image components, building blocks for our recognition of forms, patterns, faces, and other complicated images. It’s believed that a critical amount of vision might be needed to suppress activation of these images in the brain’s visual pathways. Without this dampening, the raw neurological activity may be unmasked or released, so to speak, creating hallucinations. Studies in the 1990’s determined that CBS hallucinations do indeed co-opt the same neural pathways we use to process what we see. This is likely why they usually seem so vivid and real.

CBS can develop from a number of eye disorders such as glaucoma, cataracts, or often with macular degeneration, as in my mother’s case. It’s been reported during short-term visual deprivation due to physical barriers, such as the application of temporary eye patches or other dressings after eye surgery. It can even develop from the mechanical pressure of pituitary tumors on nearby optic nerves.

But it also sometimes results from damage to areas higher up the neurological pathway, all the way to the visual cortex in the rear of the brain, in the occipital lobe. This area is involved in some cases of hallucinations, especially when it’s subjected to direct activity such as ongoing epileptic seizures. CBS can also occur from a variety of conditions that impact blood flow in the region: blockage caused by a clot, the inflammation of encephalitis, an occipital mass compressing the tissues.

The syndrome can develop at any age, though is most often seen in the elderly. Its visions may occur only once as a single hallucinatory experience, or they can persist for years. But for now, there is no cure for CBS. Encouragingly, the symptoms have been responsive to a number of experimental medications, and the search continues for the most effective way to treat them.

Fortunately, those who experience these visions are usually fully aware that they aren’t real. This is yet another clue that they are neurologic rather than psychiatric. In fact, in addition to the other two cardinal symptoms of vision loss and recurrent hallucinations, this level of insight is one of the three basic criteria required to make a correct diagnosis of CBS.

But sadly, where there is this amount of insight, there’s bound to be fear for one’s mental health. This worry is very common among CBS patients, and it can impact their willingness to report hallucinations, lest they be thought insane or demented. By current estimates, it’s believed CBS affects somewhere from 10% to 40% of the elderly population who have visual loss. But the actual number may be considerably higher because of this reluctance to report symptoms.

To make matters worse, recent surveys have shown a very low level of awareness of Charles Bonnet syndrome among patients with retinal disorders. Many people will likely suffer in silence, afraid for their sanity but even more fearful of the doctor’s potential diagnosis.

It is precisely this kind of distress that makes it so important that medical staff, caretakers, and especially the patients themselves are educated about this disorder. And if a patient does go on to develop hallucinations, kind reassurance that these strange visions are benign can go a long way to help soothe anxiety in someone already suffering from the devastating blow of permanent vision loss. For now, compassion is the best CBS medicine we have to offer.

_____

Mom has lived with her hallucinations for many months now. When she finally described them to her doctors, their oddness in the face of her otherwise clear mental status had them baffled. But eventually, one late winter morning, a diagnosis was made.

That afternoon, I arrived just in time to see volunteers wheel her, beaming, down the hallway towards her room. She loves Bingo, and thanks to the jumbo-sized numbers on the cards, she can still enjoy playing the game. She was delighted at that day’s big winnings.

But this wasn’t the only reason she was happy. After watching the nurse carefully lock away her Bingo loot, Mom turned to me excitedly. “You won’t believe it,” she said. “I saw the eye doctor this morning, and he said I have that Charles syndrome! He knew right away!”

And with that, the diagnosis was official.

My mother gets some eccentric phantom visitors. Bonnet Girl, as we jokingly call her, still arrives daily in her finest millinery. She’s now accompanied by a new boyfriend, not quite so charming. This scruffy guy has “one big ugly eye that sticks out,” and greeted Mom that morning in the activities room. But later a very real — and thankfully, better looking — young man came to see her, too: the ophthalmologist. Having many CBS patients of his own, he spotted the peculiar signs and symptoms immediately.

For Grace, coping with end-stage macular degeneration is a constant challenge, to say the least. Each day her vision seems worse, though doctors will see no further clinical change. But Mom is determined to enjoy life as best she can. Although sometimes exquisite, sometimes grotesque, she accepts her fantastic illusions for the harmless figments they are. She returns, for awhile, to a world with clear faces and vibrant details. And now that she has a name to call this illness, she takes comfort in knowing she’s not “crazy,” after all.

It’s just life with Charles.

11 Monday Jan 2016

Posted in Artful

The invention of photography profoundly changed both art and science, forever altering our way of representing and archiving our world. We may take its value for granted now, but after its birth, photography created tremendous controversy before finally becoming accepted as the expressive and versatile medium it is today. While its more practical uses were quickly adopted, it took years of exploration and experimentation for us to tap into the true depths of its artistic potential. It’s an aesthetic adventure we still continue today, the instant gratification of modern photographic technology giving us even greater incentive to capture, illustrate, and create.

The Dawn of Photography

The earliest to perfect the photographic process were Joseph Niepce and William Talbot, both scientists, and Louis Daguerre, a painter who had a long-time working partnership with Niepce. All of them experimented with complex chemical processing methods, each making their own unique and vital contribution. But it was the culmination of Daguerre’s work in 1839, the daguerreotype photograph, which first created tremendous public awareness and enthusiasm, a veritable “daguerreotypomania.”

Today, it’s hard for us to imagine what an absolute novelty it was to gaze at a photograph. Such a novelty, in fact, that when Talbot published his 1844 book, “The Pencil of Nature,” it became the first publication in history to be illustrated with photos. This viewing experience was so new that Talbot, in his introduction, had to remind his readers that his plates were

…impressed by the agency of light alone, without any aid whatever from the artist’s pencil. They are the sun-pictures themselves, and not, as some persons have imagined, engravings in imitation.

Talbot proceeded to make great efforts to protect the rights to his own photographic method, the calotype or talbotype. But in the end, it proved impossible to compete with the daguerreotype’s technical and aesthetic superiority. The French government eventually purchased Niepce’s and Daguerre’s rights to their new process. Comprehending its profound importance, France then released it, worldwide, without patent. A new visual revolution had begun.

Growing Pains

Early photographs were met with vehement protests by many, ranging from lofty philosophical objections that they were an insult to God to more down-to-earth aesthetic complaints about their graphic and, at times, downright ugly honesty.

But many forward-thinking enthusiasts were thrilled at the exciting potential of the new invention. Edgar Allan Poe, himself the subject of a number of well-known and iconic daguerreotypes, wrote several periodical essays in 1840 devoted to the subject. He felt adamantly that these new, truthful images provided a kind of insight into human nature itself, and “…must undoubtedly be regarded as the most important, and perhaps the most extraordinary triumph of modern science.” And as their popularity grew, an ever-increasing number of the population became able to view and purchase these images for themselves.

Via Wikimedia Commons Source: Wonders & Marvels

But one important impediment to public access still remained. Creating a daguerreotype was a very specialized and labor-intensive process, involving knowledge of complex arcane procedures and the use of potentially dangerous chemicals. This meant that only a relatively few expert photographers were able to actually take and develop their own photos.

Then entered George Eastman, American philanthropist and entrepreneur, who perfected the first practical roll film and produced the Kodak camera in 1888. This standardized the process, and its ease of use now made it accessible, virtually overnight, to anyone. No longer was photography in the exclusive domain of a handful of highly skilled individuals with very specialized abilities. It now belonged to amateurs and professionals alike.

Art or Science?

This new ubiquity deeply fanned the flames of an already intense debate within the artistic community about whether photography could ever truly be considered an art form. There were many who felt it would always remain simply a product of inexpressive and passionless chemistry. But this longstanding and heated controversy would continue to rage on in vain as photography began to quietly but profoundly change the way we creatively see our world.

Perhaps nowhere was this change in vision more clear than in the work of the Pre-Raphaelites. Originally founded in 1848, this brotherhood of artists shunned classical mannerist painting and revered historical periods of art before the appearance of such artists as Raphael and Michelangelo. They were heavily influenced by the aesthetics of 15th-century Italian art and were moved by the ideals of Romanticism and the spirituality of the medieval period. Nature was also of the utmost importance, and they believed that very careful rendering and “mimesis,” the accurate imitation of natural forms, were crucial to the message they wished to convey. Like the early photographers, they searched for new and creative ways to employ realism. But as a reaction to photography, they were challenged to take their painting to philosophical and symbolic realms beyond its reach. The result was a strongly photorealistic quality to their dream-like work, made almost hyper-real through their intense attention to postures, textures and details.

John William Waterhouse – The Crystal Ball Via: Wikimedia Commons Source: WikiArt

The impressionists also felt the strong impact of the photographic revolution. As they pushed the boundaries of conventional visual art, many painters took advantage of a new vocabulary of photo-like effects such as motion blur, the use of new and dramatic angles of view, and the extension of subjects beyond a painting’s boundaries. And as the ordinary subject matter of most photographs began to foster a new interest in the everyday activities of common people, many impressionists responded in kind by focusing on such egalitarian themes in their own work. Exploring in parallel evolution with the photographers of their time, each found brand new ways of creating a sense of spontaneity and expressing the truth of captured living moments, frozen in time.

Gustave Caillebotte – Segelboote in Argenteuil Via: Wikimedia Commons Source: The Yorck Project

Yet other artists, still unmoved by the starkness of early photographic imagery, began to use photos simply as reference sketches for their paintings, building on that strictly representational material and turning it into a more subjective and expressive work. But gradually the tables turned, and conventional concepts and sensibilities of fine art now, for the first time, began to impact photography.

The Poetry of Pictorialism

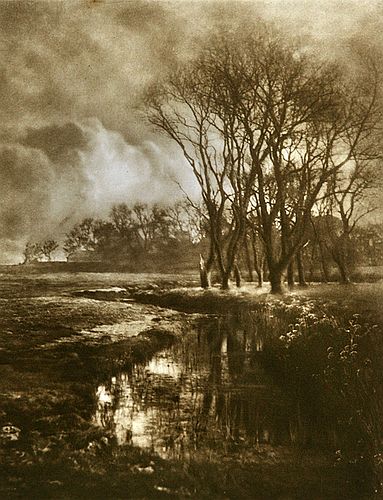

A fascinating artistic movement arose in the late 1800’s now known as “pictorialism.” This would prove to be the first important turning point in the development of photography as an art form, demonstrating to viewers that it was now capable, definitively, of being more than just a means to record reality.

Searching their way through this still-new medium for a means of greater expression, a small circle of like-minded photographers strove to create what they saw as more evocative, artistically relevant work. During the last decade of the 19th and on into the early 20th century, this movement blossomed into international prominence as a growing number of pictorialists found new and ingenious ways to imbue their subjects with sentiment and imagination. They experimented with creating a sense of atmosphere to soften harshness, using soft focus and choosing sepia or blue tones rather than basic black and white. They carefully adjusted tonality to further enhance a sense of mood. In effect, they distanced viewers just enough from the subject matter to allow them room to use their imagination, thereby giving them a more active role in the artistic process.

Motif from Suffolk – Alfred Horsley Hinton Via: Wikimedia Commons Source: Luminous-Lint

Fast Forward

The initial allure of the pictorialist movement gradually began to fade by around 1920. Modernism, with its emphasis on sharp focus, changed aesthetic tastes and rendered its sensibilities old fashioned. Even the great fine art photographer Alfred Stieglitz, one of pictorialism’s most fervent creators, eventually rejected its methods for their inherent artifice. He went on to help establish a more modern approach to the medium, feeling that photography could be impactful on its own, through the skill of the photographer himself, without resorting to darkroom tricks. Fine art photography was now maturing and moving in a new direction through great photographers like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, to be followed in turn by the well-known portraiture and photojournalistic artists of the later 20th century and beyond.

But there has now been a resurgence of interest in the earliest photography. Many of us have found joy in rediscovering both the romantic creativity of pictorialism and the poignant realism of daguerreotypes. And though this may seem anachronistic, it really makes perfect sense amid the endless expressive possibilities available in our contemporary world of digital cameras, phones, and processing apps. Though many of the techniques and effects of the early photographers are naive by today’s standards, with a quaintness that is an inevitable result of being a product of their time, their sheer inventiveness and raw freedom of expression still speak to us. As pioneers ourselves, their ground-breaking discoveries resonate with us as we continue to invent, as they did, even more compelling ways to create photographic art.

Nature’s pencil will never stop sketching as long as new inspiration and technology await.

Photo: Barbara Gowin

15 Tuesday Dec 2015

Posted in Healthful

We instinctively know them when we feel them. Sensations of peace, wholeness, connectedness. Those moments when we travel to that still, quiet place in our minds, a place where more and more healthcare professionals are now asking us to visit. They ask this because there is some very solid science out there confirming that the mind can have a profound effect on wellness.

You see, in terms of human evolution, the body’s stress response is an excellent survival strategy for getting us through an acute crisis. But as it turns out, it’s not such a great strategy when we leave it playing at low volume in the background for years.

Vascular disease, diabetes, stroke, immune suppression, and a myriad of other stress-related physical problems remind us that, even though we have put the nightmares of some of the most deadly diseases in history behind us, we now have another assortment of illnesses that can break us in new and different ways.

But it’s never too late to start to mend what’s broken. Taking the first steps down the road to well-being is something each one of us can achieve.

THE BEAUTY OF PLAY

Okay, Stress, it’s time for you to meet your new playmate: Creativity.

We are, all of us, capable of being creative. Self-expression is a vital part of who we are…who YOU are. Don’t you think it’s time that the real you — the one that’s still there, buried down deep underneath all that stress — came out to play?

For me, photography has a big role in such play. It mobilizes me to seek out places I might not otherwise visit. It slows me down and gives me permission to linger. Sometimes it literally makes me stop and smell the roses.

If you, too, like to photograph, go ahead and express yourself. What do you want to say? Do you want to bring out the essence, the “itness” of what you see? Challenge yourself and think about different ways to do that. Want to zero in on just one defining aspect? Emphasize whatever feature is most important to you and hold it up for our inspection. Fascinated by those simple, small moments that speak volumes about what it means to be human? Go capture some. They’re happening all around us.

No need for expensive equipment, if that’s not your thing. I just use my iPhone, because there’s no denying the simple truth: The best camera is the one you have with you.

What ignites YOUR passion? Only you know best those things that are nearest and dearest to you. Allow yourself to take some time and explore them. Seek out their beauty, if for no other reason than your own self-preservation. Write, draw, sing, dance. Allow your voice to be heard.

And take a good, long whiff of those roses.

13 Sunday Dec 2015

Posted in Museful

What do you want to be when you grow up?

This can be a downright agonizing question for a generalist. Tugged at by so many interests, choosing a single focus can mean leaving so much neglected and undiscovered.

I have always been drawn to both art and science. But like many others, I’ve struggled to somehow choose between what appear to be two opposing disciplines. Now, the more I learn, the clearer it becomes that these two are not at odds, after all. That notion is far too simplistic. They are really on a long continuum, each expressing a different way of approaching the same fundamental human questions and needs.

So I’ve made a choice NOT to choose. And there may be no better time than the present to make that decision.

For we are at a turning point, entering into an era that promises an unprecedented rate of human progress, and hence, the need for equally speedy human adaptation. Now, more than ever, we need the input of both artistic and scientific perspectives to help us move gracefully through such great paradigm shifts. To form them into shapes that resonate with us and make us eager to embrace them. Only in this way will we ever truly become one with our technology.

Art + Science = Beauty

I also believe that deep at their roots, motivating and uniting each discipline’s separate approach is our inherent appreciation of, and endless search for, beauty itself. And though specific concepts of what constitutes beauty in art and science often differ in quality, they don’t differ in quantity. Aesthetic ideas and motivations are abundant not only in our artistic creativity but also in our joy of scientific discovery, and both studies can be equally capable of evoking a powerful emotional response.

The late Richard Feynman, beloved and outspoken twentieth-century physicist, relates his own scientific appreciation of beauty with obvious passion during a famous BBC interview from 1981:

The more we learn about our world and ourselves, the more layers of beauty we find to enjoy. That, in turn, drives us to uncover ever more layers. They can be found everywhere and across all disciplines. The thrill of this search is a vital part of what makes us human, of what gives our lives meaning. It compels us to dream, experiment, and create. It drives us to learn our purpose and our place among the stars.

Even those of us who may never decide exactly what we want to be when we grow up.